We're right on the

cusp of another generation of game consoles, and whether you're an Xbox One fanperson or a PlayStation 4 zealot you probably know

what's coming if you've been through a few of these cycles. The systems will

launch in time for the holidays, it will have one or two decent launch titles,

there will be perhaps a year or two when the new console and the old console

coexist on store shelves, and then the "next generation" becomes the

current generation—until we do it all again a few years from now.

For gamers

born in or after the 1980s, this cycle has remained familiar even as old console

makers have bowed out (Sega, Atari) and new ones have taken their place (Sony,

Microsoft).

It wasn't always this

way.

The system that began

this cycle, resuscitating the American video game industry and setting up the

third-party game publisher system as we know it, was the original Nintendo

Entertainment System (NES), launched in Japan on July 15, 1983 as the Family

Computer (or Famicom). Today, in celebration of the original Famicom's

30th birthday, we'll be taking a look back at what the console accomplished,

how it worked, and how people are (through means both legal and illegal)

keeping its games alive today.

From Japanese

beginnings to American triumphs

The Famicom wasn't

Nintendo's first home console—that honor goes to the Japan-only "Color TV

Game" consoles, which were inexpensive units designed to play a few

different variations of a single, built-in game. It was, however, Nintendo's

first console to use interchangeable game cartridges.

The original Japanese

Famicom looked like some sort of hovercar with controllers stuck to it. The

top-loading system used a 60-pin connector to accept its 3-inch high, 5.3-inch

wide cartridges and originally had two hardwired controllers that could be

stored in cradles on the side of the device (unlike the NES' removable

controllers, these were permanently wired to the Famicom).

The second controller

had an integrated microphone in place of its start and select buttons. A 15-pin

port meant for hardware add-ons was integrated into the front of the

system—we'll talk more about the accessories that used this port in a bit.

After an initial hardware recall related to a faulty circuit on the

motherboard, the console became quite successful in Japan based on the strength

of arcade ports like Donkey Kong Jr. and original titles like Super

Mario Bros.

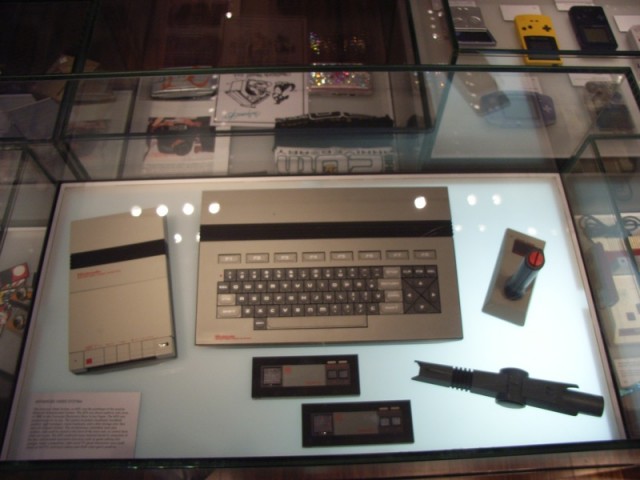

Enlarge / An early prototype of what

would become the North American version of the Famicom. The Nintendo Advanced

Video System communicated with its peripherals wirelessly through infrared.

The North American

version of the console was beset by several false starts, to say nothing of

unfavorable marketing conditions. A distribution agreement with then-giant

Atari fell through at the last minute after Atari executives saw a version of

Nintendo's Donkey Kong running on Coleco's Adam computer at

the 1983 Consumer Electronics Show (CES). By the time Atari was ready to

negotiate again, the 1983 video game crash had crippled the American market,

killing what would have been the "Nintendo Enhanced Video System"

before it had a chance to live.

Nintendo decided to go

its own way. By the time 1985's CES rolled around, the company was ready to

show a prototype of what had become the Nintendo Advanced Video System (AVS).

This system was impressive in its ambition and came with accessories including

controllers, a light gun, and a cassette drive that were all meant to interface

with the console wirelessly, via infrared. The still-terrible market for video

games made such a complex (and, likely, expensive) system a tough sell, though,

and after a lukewarm reception, Nintendo went back to the drawing board to work

on what would become the Nintendo Entertainment System we still know and love

today.

Enlarge / By late 1985, Nintendo had

settled on the console design that most American readers will be the most

familiar with.

What Nintendo went to

market with in October 1985 wasn't just a console redesigned for a new

territory, but a comprehensive re-branding strategy meant to convince

Westerners that the NES wasn't like those old video game consoles that had

burned them a few years before. This new Famicom was billed as an

"entertainment system" that required you to insert "game

paks" into a "control deck," not some pedestrian video game

console that took cartridges. The console's hardware followed suit—it was still

marketed to kids, but the grey boxy Nintendo Entertainment System looked much

more mature than the bright, toy-like Famicom. At the same time, accessories

like R.O.B. the robot assured parents that this wasn't just for "video

games"—still dirty words to many consumers.

Note the drastic differences between

American and Japanese game cartridges. The disk card pictured here was intended

for use with the Japan-only Famicom Disk System.

Each of the titles in

the relatively strong 18-game launch lineup (remember, at this point the system

had been humming along for more than two years in Japan) also featured box art

that accurately depicted the graphics of the game inside, unlike the

disappointing exaggerations of the Atari 2600 version of Pac-Man or

the infamous E.T.

The final building

block in the NES rebuild of the North American game industry was the way

Nintendo handled third-party developers. In the Atari era, everyone from Sears to Quaker

Oats tried to grab a slice of the gaming pie. The fact that

basically anyone could design and sell hastily-coded Atari 2600 games with no

interference from or cooperation with Atari led to a game market flooded with

shovelware and to clearance bins filled with unsellable dreck. This in turn led

to gun-shy retailers and consumers.

Nintendo clamped down

on this hard. Third parties had to be licensed to develop games for Nintendo's

system, and Nintendo's licensing terms both prohibited developers from

releasing games for other consoles and confined them to releasing just two

games a year. Other restrictions, mostly aimed at weeding out religious and

other "inappropriate" content, were also imposed—memorably, these

restrictions resulted in the Super Nintendo port of Mortal Kombat where

all the kombatantscombatants ooze "sweat" instead of

blood. Developers agreed to the restrictions in order to get access to a base

of NES fans rabid for new software. (Many of Nintendo's restrictions weren't

relaxed until the early '90s when it was losing developers to its first

credible competition, the Sega Genesis.)

Licensed games

received both a printed Seal of Quality on their boxes and access to the

proprietary 10NES lockout hardware, a chip on the cartridge's circuit board

that checked in with a corresponding chip on the console's. While not

foolproof, in the early days of the NES the 10NES hardware helped to combat the

flood of low-quality software that had killed off Atari and its ilk.

Not all developers

were happy with these terms, but fighting Nintendo was an uphill battle. The

most significant challenge to the 10NES system came from Tengen, a subsidiary

of Atari Games. Rather than try to circumvent 10NES, Tengen used Nintendo's

copyright documents to reverse-engineer the chip and create its own compatible

version, codenamed "Rabbit." Nintendo sued for patent infringement and,

at least in part because Tengen didn't use a clean room design in Rabbit, the

judge ruled in Nintendo's favor.

Enlarge / The 10NES chip would

prevent the system from booting if its security check failed. It was important

in the early days, but NESes with dirty or worn connectors are prone to failing

its check—this led to the dreaded grey blinking screen that I've probably spent

hours of my life looking at. The redesigned top-loading NES shipped without a

10NES chip, and some people who repair older NES consoles recommend snapping

off the fourth pin of the chip to disable the check entirely, as shown here.

Salvaged Circuitry

And the rest is really

history. The NES was the undisputed leader in the US for several years and

wasn't seriously challenged until Sega's Genesis kicked off the 16-bit era. In

some territories like Europe and South America, the 8-bit Sega Master System

had gained a stronger foothold, but it was a relative rarity in the US. A new

top-loading version of the NES and the Famicom with a redesigned controller was

launched in both America and Japan in 1993 after the introduction of the Super

Nintendo, but by then the stream of high-profile software had slowed to a trickle.

The system was produced until 1995 in the US but lived to see its 20th birthday

in Japan before being discontinued in 2003.

No comments:

Post a Comment